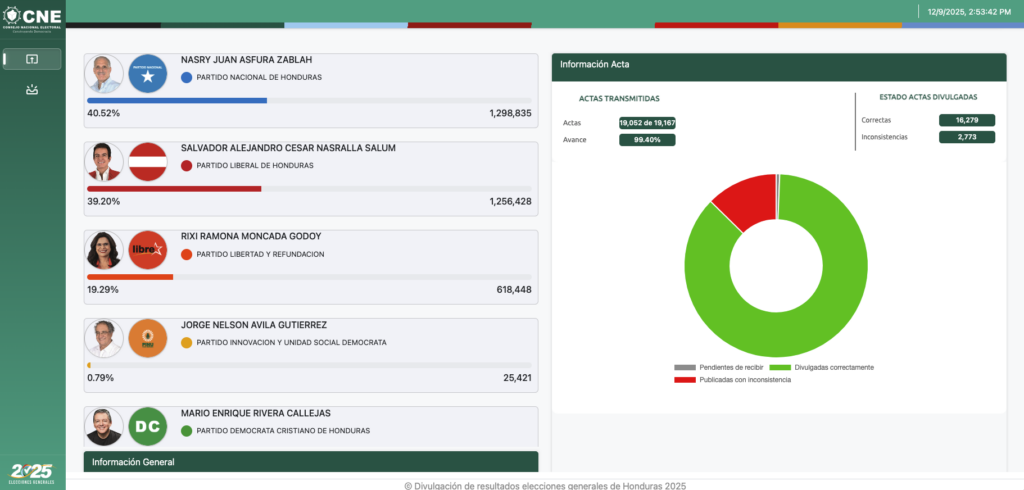

Costa Rica’s President Rodrigo Chaves once again narrowly avoided losing his presidential immunity, a shield against investigation that remains firmly in place despite mounting allegations. The recent December 16th vote in Congress revealed a deeply divided legislature, falling just short of the votes needed to allow a probe into claims of improper political maneuvering.

The controversy centers around accusations of “political proselytism” – a serious offense in Costa Rica, defined as public officials using their power to benefit a political party or engage in prohibited electoral activities. Fifteen complaints filed by the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) triggered the attempt to lift Chaves’ immunity, igniting a fierce debate within the halls of power.

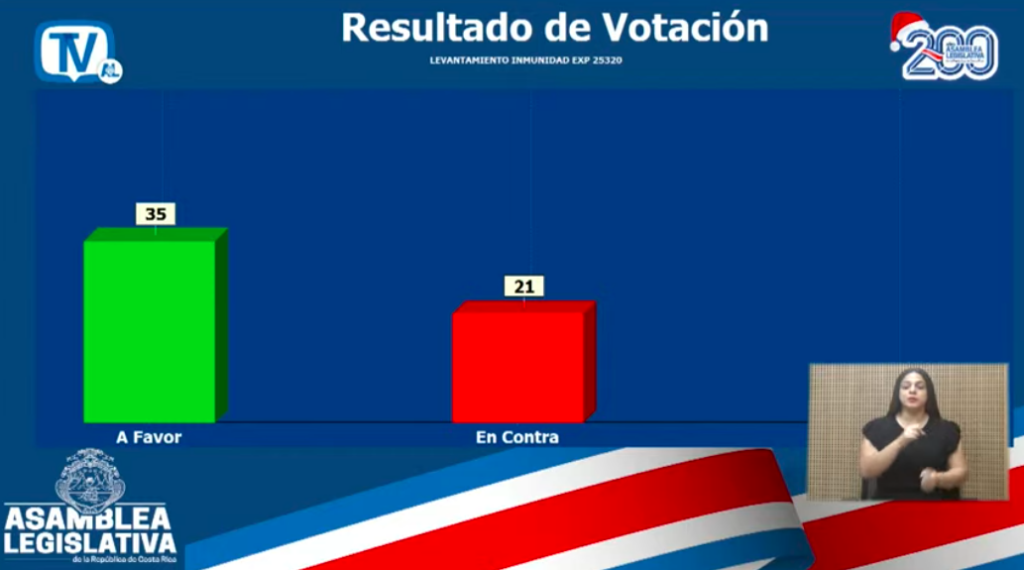

While a key congressional committee recommended removing the president’s protection, the full legislature couldn’t muster the required 38 votes. The final tally – 35 in favor, 21 against – underscored the intense political stakes and the difficulty of pursuing such a challenge against a sitting president.

Lawmakers supporting the investigation argued there was “sufficient evidence” to warrant a deeper look by the TSE. They stressed the process wasn’t about removing Chaves from office, but about ensuring accountability and allowing due process to unfold regarding the serious allegations.

Alejandra Larios, chair of the special committee, painted a stark picture of potential abuse. She warned of a “significant risk of using public power to influence the popular will” ahead of the 2026 elections, citing evidence found within official presidential communications. The concern was clear: public resources allegedly being diverted to influence the electoral process.

President Chaves’ defense team countered with a fundamental argument: the Constitution doesn’t explicitly prohibit “proselytism,” only “political bias.” Attorney Daniel Vargas Quiroz argued this wasn’t a mere semantic difference, but a crucial legal distinction, claiming there was no legal basis to punish the president for the alleged actions.

However, Costa Rica’s Electoral Code directly addresses the issue, prohibiting public officials from engaging in political activities during work hours or using their position to favor any party. The code explicitly bans partisan promotion by those in power, a rule the opposition contends Chaves has repeatedly violated.

Some lawmakers vehemently disagreed with the attempt to lift immunity, dismissing the accusations as an attack on free speech. They argued that simply stating the need for a certain number of lawmakers in the next government wasn’t an offense, but a natural part of democratic discourse.

The outcome was largely anticipated, with reports surfacing last week that key lawmakers planned to withhold their support. Concerns were raised that pursuing the case would disrupt the upcoming 2026 electoral campaign, highlighting the delicate political balance at play.

This isn’t the first time President Chaves has faced such a challenge. Earlier in the year, in July, the Supreme Court requested Congress lift his immunity to investigate allegations of corruption related to a questionable contract awarded to a communications firm.

That request, involving a $405,000 contract and accusations of abuse of office, also failed in September. The vote – 34 in favor, 21 against – marked a historic moment as the first time Costa Rica’s Congress voted on removing a president’s immunity.

The Attorney General’s Office has stated it will wait until Chaves leaves office to pursue the corruption case in a criminal court. For now, the president remains protected, leaving a cloud of uncertainty hanging over his administration and raising questions about accountability in Costa Rican politics.